Are you one of the people that find following Jesus in this day and age challenging? Are you scared? Overwhelmed? Are you frustrated about church hierarchy or restrictive Christian beliefs? Does consumerism and the climate emergency make you feel trapped? Do you feel overburdened by the responsibility of inspiring faith in your children while your own connection with Jesus seems to dwindle? Well, you are not alone! Countless Christians of the past and present can more than relate to your sentiments.

So, as a small offering, I’d like to introduce you to an outlook on life and faith that may resonate with you. It addresses the above-mentioned grievances and incorporates stirrings many of us feel deep within: love for nature, and a longing for an intuitive, liberating and simple prayer life. All this comes together in Franciscan spirituality. This isn’t a set of fixed rules, but, as one writer said, ‘a way of dealing with the universe’ by ‘catching on to the rhythm of things’.

Franciscan spirituality is based on the notion that the natural world isn’t an afterthought of God’s power and being. No, it directly flows from the heart of an infinitely loving creator. Franciscans view creation as ‘sacramental’, meaning God encounters us within and through all created things. Because God became a human being on planet earth the whole cosmos ‘oozes’ divine presence, with Christ at its centre.

Humanity, nature (even inanimate rocks!) and Christ himself are deeply interconnected: there’s no division between ‘ordinary’ and ‘holy’. St. Francis’ ‘Canticle of the Creatures’ (which celebrates its 800th birthday this year!) beautifully expresses this togetherness: ‘Praise be my Lord by means of Brother Sun (…) Sister Water (and even) sister Bodily Death’.

Of course, this loving attitude spills into the Franciscan view of humanity. Because God’s divine presence radiates through every single individual, Franciscan thought and action emphasise love and care for the poor and marginalised.

Let’s get into some historical background. As the name suggests, these ideals were popularised by St Francis of Assisi, Christianity’s probably most cherished saint. (You surely have seen artwork of him mingling with birds and other animals!) He grew up in 12th century Tuscany, a reportedly charming, fun-loving and privileged young man, who was fascinated by all things chivalrous and military. His conversion process began with a year-long imprisonment, a serious illness and his dawning awareness of the appalling living conditions of the poor. After defining moments of embracing a leper and perceiving God’s voice speaking to him, he broke with his family and lived a life of poverty and service.

Attracted by his joy and authenticity, soon others joined him as ‘brothers’, living primitively, working with peasants, caring for the sick, and preaching. This ‘life of penance’ was fuelled not by asceticism, but a longing to follow Jesus and the apostles. Francis was deeply compelled by Jesus’ humility, love, and suffering, and believed in the goodness and interrelatedness of all creation.

Fundamentally, the Franciscan movement responded to issues within the church which are also criticised by some nowadays: hailing tradition over innovation, insurmountable hierarchies, unhealthy ties with politics, and compromised values. Also, the Franciscan movement is inherently inclusive of women and lay people, starting with St Clare, a close friend of Francis and founder of the women’s order. The so-called ‘Third Order’ of Franciscans—communities of lay people living in their own homes and families—also developed already during Francis’ lifetime.

So, what does it all look like these days? All three religious orders (friars, sisters and ‘secular’) are active globally to this day (not only Roman Catholic, but also Anglican and Lutheran) and often describe themselves as ‘contemplatives in action’. However, the Franciscan way of life also guides many Christians outside formal communities, who recognise God’s presence in all creation and people, embrace simple living, serve others, and care for the planet. Serving the poor and marginalised and caring for the planet are intrinsic Franciscan practices. These principles give permission to recognise love for creation and social justice as essential to one’s spirituality.

Acknowledging Christ’s presence in creation, the Franciscan way can open hearts to fresh encounters with Jesus. Small first steps could be trying to become mindful of Christ in all things and people: in the doctor’s waiting room, walking to the shops, or when gardening. Franciscan simplicity can look like (even just temporal) technology ‘detox’, a simplified diet, or ethical financial spending. These not only support many people’s longings for more sustainability but can be powerful spiritual practices drawing them closer to God.

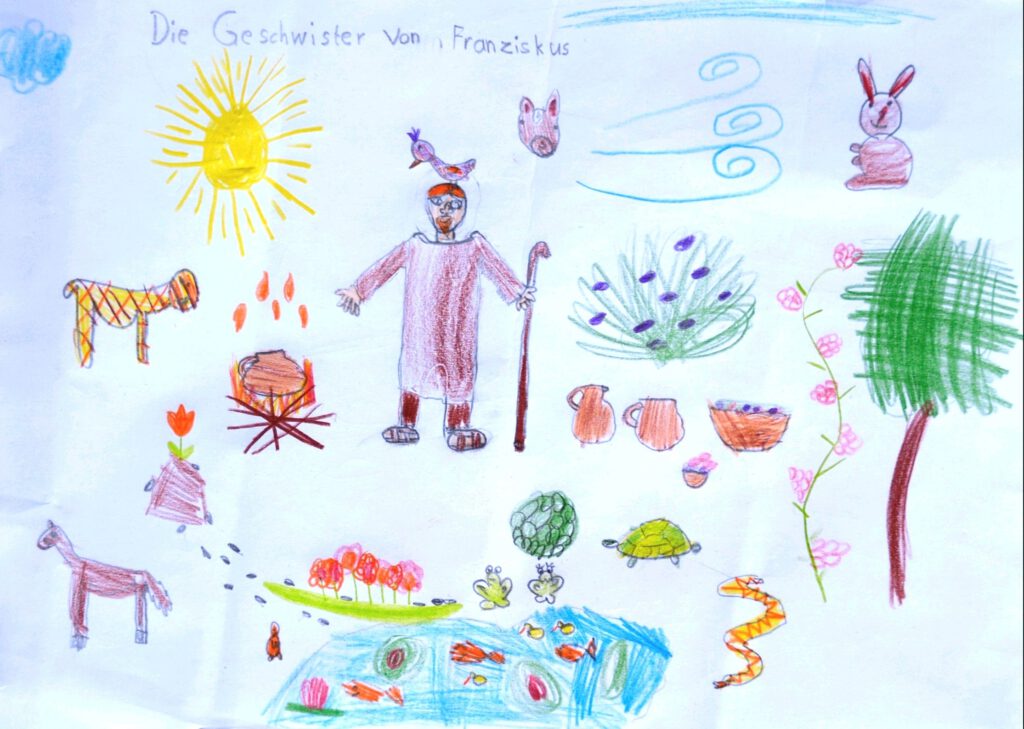

Also, it is wonderful to explore Francis and Clare’s life and legacy with the whole family. I find children connecting easily with Franciscan stories and thought. (See the attached drawing by my 8-year old!). Interestingly, in 1223 Francis himself created the first iteration of a beloved Christian all-age tradition: a nativity scene to visualise God entering ordinary creation and humanity. As a mum, I find the following thought by the early 3rd Order Franciscan Angela of Foligno validating and inspiring: Herself a wife and mother, she perceived the world as ‘pregnant with God’. How lovely is that!?

All this being said, naturally, there are some caveats. Firstly, Franciscan spirituality may possibly come across as a ‘St Francis cult’, or as being shallow or naive. However, Francis can’t be reduced to a simplistic concept, but is indeed quite challenging. After all, he was a radical in ‘decluttering’ the gospel, in choosing poverty, and in embracing all people and created things. Unsurprisingly, the Church soon moved away from many radical aspects, and already his canonisation (meaning him being ‘sainted’ just two years after his death) featured much pomp. The Franciscan movement itself, too, has understandably developed into an institution which, at times, had lost some of the spirit of poverty and simplicity. Nevertheless, contemporary Franciscans do incredible work, and are often unconventional in challenging and inspiring society.

Furthermore, some dismiss Franciscan spirituality as kitsch or ‘pop spirituality’, overlooking its brilliant academics, devout practitioners and renowned Christian leaders. Still, idolisation of creation is a real risk, even if Francis never viewed creation as ‘heaven on earth’, but a fellow-pilgrim back to Christ. This attitude has nothing to do with ‘hashtag asceticism’ or ‘green washing’, but with real humility of someone who, as Francis’ Pope Innocent put it, ‘merely wished (people) to live by the gospel.’

Francis’ vision of the gospel is helpful to Christians in various ways. Not only ‘his’ pope, but also generations of writers and historians understood that his approach to life and faith struck a nerve with his contemporaries. Then as now the Franciscan way hits home with people’s hopes and frustrations. It shows how Christianity can speak powerfully into the realms of politics, commerce, society, and ecology. It connects Christians with all ‘people who care’: scientists, artists, activists, NGOs, and ordinary folks striving for mindful and moral lives.

Clearly, ecology is the most obvious area of Franciscan influence, especially after 1979, when St Francis was recognized as patron saint of ecology. I believe that he can be a meaningful guide in our growing ecological crisis; a crisis in great part caused by certain Christian ideologies, that took (and still take) the words from Genesis 1:27-28 (“Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it…”) as a command to violate the planet. Franciscans experience the destruction of our planet as destruction of ‘Godself’ and every extinct species as the loss of God’s footprints. As it recognises nature’s intrinsic value and interconnectedness, Franciscan ‘eco-penance’ promotes liberating and joyful environmental justice—just how authentic faith ought to be felt and lived!

The Franciscan tradition also upholds surprisingly modern and just approaches to pertinent concerns of society and church. Just think of the 3rd Order Franciscans’ inclusivity in terms of social diversity and lay vocation, and Francis’ radical nonviolence. In times of growing economic overshoot many rightly long for a simpler lifestyle. They all can see themselves in the company of Francis (who promoted a kind of circulation economy and experienced wealth as captivity, not security) and Clare (who knew what it meant to fight off assets of an apparently well-meaning system).

Francis knew the feeling of disillusionment with church and society, and experienced how God can create beauty out of it. He once described how ‘no one showed him what he was to do’, meaning he, like most of us, hadn’t got a grand plan, but instead followed Christ’s lead. Clare set a wonderful example of how to find one’s place in life by aspiring to reflect Christ without idolising Francis. She wrote about how ‘the Son of God has been made for us the Way’ which Francis ‘has shown and taught’.

Dear friends, I’ve got the feeling that some of you, too, would enjoy exploring this ‘way that Francis showed’. Perhaps listening to God speaking to you through the ‘book of creation’ will be a way of reconnecting with Christ. You may find it naturally resonating with your innate motivations and aspirations.